|

Lt. Col. Louis Francis Burleson, USAF

Louis Francis Burleson was born on November 30th

1914 in a farm house in New London North Carolina. Louis was the

last child of Corinna and J. V. Burleson, being born when J. V. was 44

years-old. Louis was a very athletic young man and earned high

school letters in football, basketball and baseball.

A good

student, at 15 years old he went to live in New York City and his name

appears in the 1930 US census, living on Lexington avenue with his

sisters Mary and Sarah. He returned to New London and graduated from

High School in 1932.

|

Louis F. Burleson

|

In 1935 Louis Burleson joined the US Army Air Corp and was

stationed with the 8th pursuit group in Hawaii for six years, where he learned

aircraft mechanics and served as pitcher for the Army baseball team.

Here he served as a crew chief for the P-36 and P-40 fighter

aircraft.

These were the days when Hawaii was still an unspoiled paradise.

|

|

Early Air Corp service

Gifted with a photographic memory and a natural

ability in mathematics, Louis supervised poker games in the

casinos on Waikiki beach. By taking 10% of each pot to keep the

game honest, Louis earned over $1,000 per month, far more than his

meager military pay of $36/month. By 1938, Louis was promoted to

sergeant, earned his pilots license and had a nice off-base apartment

on Waikiki beach, where he hired a Navy Captain's wife to do his

cleaning.

In 1941 Louis F. Burleson was transferred to

Kirtland Field in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

It was there in 1941 that he met

Virginia Geraldine Burleson

(then Virginia Rylance (Griffiths)), a whirlwind romance culminating

in their marriage in September 1941, less than 90 days before Pearl

Harbor and the outbreak of WWII.

His new wife, Virginia (Ginger) Griffiths

immigrated from Ireland, and was born on Feb 15th, 1920 in Dublin, the

daughter of Geraldine and Charles Griffiths. Charles died at sea

in 1919 when returning from Australia

Virginia then immigrated to the United States with

her mother, widow Geraldine Burns to New York City in 1920. Her

mother re-married in about 1932 and became Geraldine Rylance, moving

to Albuquerque New Mexico.

Less than a week after their wedding, Louis was

promoted to Technical Sergeant and transferred to Clark Field in the

Philippines where he was assigned to the 19th bomb group of the 5th

Air Force as a mechanic for the fleet on several dozen B-17 bombers.

It was at Clark Field where Louis first encountered

combat when he fought the Japanese on December 7th, 1941. The

Japanese had leaked news of their attack on Clark Field prematurely,

giving the airmen a brief heads-up on the impending sneak attack!

Listening to radio reports of the attack at Pearl Harbor, the radio

announcer also said that Clark Field had also been bombed, even though

it was quiet at Clark Field.

|

Taking the hint, the B-17s were quickly moved to a

safer area, but less then 10 minutes after the announcement a wave

of more than 50 Japanese bombers devastated Clark Field,

destroying more than half the U.S. air power in the Pacific

theater.

After the cowardly attack, a single P-40 was

idling at the end of the runway. Louis was horrified that the

pilots head was blown clean off, and he had to reach over the

bloody pulp to shut down the engine. |

|

As the Japanese invaded the Philippines, Louis fled

to the island of Luzon where the last holdouts prepared a

stand against the Japanese invaders. After General Macarthur

was order to leave Luzon, morale declined as the Americans

were short on food and supplies and vastly outnumbered by the

Japanese.

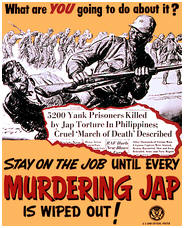

Many of those who remained were murdered in the Bataan death

march, a Japanese war crime where only 54,000 of the 72,000

American POW's survived to reach their destination .

|

WWII Service Notes:

Clark Field, December 1941 |

Louis Burleson was ordered to take the last ship

from Luzon, leaving his compatriots to face certain defeat.

Those left behind were captured and were forced to

march north though the jungle in the infamous “Bataan Death

March”.

Louis Burleson was evacuated to

Darwin Australia in a B-24 on January 27, 1942.

|

February 16, 1942 - Six B-17 of the 19th Group

took off from Malang at 0830 to attack enemy forces in the Telang,

Moosit and Oelang Rivers.

|

No. 2455

|

|

Mathewson

|

|

Scarboro

|

|

Wood

|

|

Burleson

|

|

Gardner

|

|

Elder

|

|

Clevenger

|

|

Hale

|

February

19, 1942

- Crews and planes were

prepared for 0630 take off. At 0230 the bomber command ordered three

planes to take off as soon as possible and the others at dawn. The

target was given as 4 cruisers and two transports on the south coast

of Bali. The first three airplanes were to bomb at night individually

with single bombs. The first three planes cleared the airdrome at

0500.

|

No. 2484

|

|

Mathewson

|

|

Scarboro

|

|

Wood

|

|

Burleson

|

|

Gardner

|

|

Routher

|

|

Lyday

|

|

Elder

|

These planes with the same crews departed Malang at 1240 for

second mission of the day to Den Passac and Bali.

February 22, 1942

-The 19th

Group sent two B-17Es against the Denpasar Airport on Bali,

|

No. 2472

|

|

Mathewson

|

|

Scarboro

|

|

Wood

|

|

Burleson

|

|

Gardner

|

|

Routher

|

|

Lyday

|

|

Elder

|

|

The 19th

bomb group suffered heavy losses from the daring daylight raids and

they sought to undertake a new bombing method that would minimize

casualties.

It was this type of

innovative thinking, coming up with new uses for existing tools

that helped win the war in the Pacific.

The 19th bomb

group motto was "In Alis Vincimus” On Wings We Conquer.

|

On September 23, 1942,

Louis Burleson was part of a bold attack on the Japanese where the

30th squadron of the 19th bomb group

performed dive Bombing a B-17 to

sink a Japanese ship.

As a gunner on the B17’s, Lou's expert marksmanship

with the 50 caliber machine guns sent many Japanese fighter planes

crashing into the Pacific Ocean. Louis Burleson once stated that

he believed that he shot down at least ten enemy aircraft using a

technique that he discovered from the nighttime bombing raids.

Unlike the B-17 which has a protecting inner lining to seal-up bullet

holes, the Japanese fighters did not have this feature. By

loading his machine gun with incendiary rounds he was able to explode

the fighters with a well-placed shot into the wings.

Actual

Photo of the B-17 mission over Rabaul

Dive bombing in a B17

The B-17 is a large heavy 4-engine bomber, not designed to

work as a dive bomber, but we were desperate for a victory

over the Japanese, and desperate times called for desperate

measures,

using a B-17 as a dive bomber.

Rabaul harbor was a major Japanese port, heavy guarded by

Flack cannons and machine guns, impenetrable in daylight.

The only hope of a victory was to attack at night

when the Japanese gunners could not see the B-17, but the

cover of darkness worked both ways.

Even with the top-secret Norden bombsights, they

needed light to see the targets. And even if we could see

the ships, a freighter is a mighty small target from 20,000

feet.

Louis flew on the mission that destroyed a

10,000

ton Japanese troop ship by dive bombing it |

After word got out about the

Japanese atrocities at Bataan, morale was at a all

time low and a small group of heroic young airmen

decided to execute a bold attack against the

Japanese.

Major Bernard Schriever, a newly-minted Major fresh

from Graduate school at Stanford University, joined the 19th

bomb group in Australia and directed Burleson’s effort to perfect the

flare racks.

In less than 90-days Schriever recommended Louis

Burleson for an officer’s commission.

Gen. Dougherty was

the pilot of Louis Burleson’s crew on a famous

bombing raid there Schriever used the B-17 as a dive

bomber, destroying a large Japanese cargo ship in an

act of extreme heroism.

My father

designed the flare racks and volunteered to fly on

this mission as flight engineer, manning the top

turret gun on the B-17. |

This recollection of the dive bombing B-17 is from

an article about General Schriever in “Air Force” magazine:

|

Gen. Bernard Schriever |

“They flew in a formation of

about a dozen B-17's in a night raid on Rabaul.

Their airplane carried the

flares and half the regular bomb load.

The flare system worked well,

but Schriever wanted to check on the bombing results, so they made

another circuit over the target area. Flak was heavy but

ineffective at the 10,000-foot altitude from which they were

bombing."

|

Gen. Jack Dougherty |

After the Doolittle raid, the destruction of this ship was one of the

first major American victories in the Pacific war and Louis F.

Burleson was awarded his first Distinguished Flying Cross for his

achievement in this dangerous mission.

Here is the Distinguished Flying Cross citation of the B-17 dive

bombing raid from Louis Burleson's military record.

John Dougherty and crew bombed Rabaul harbor using parachute flares

designed by Louis Burleson, using a B-17 Flying Fortress as a

"dive-bomber," destroyed a large cargo ship and damaged a 10,000 ton

troop ship. Rabaul harbor was still classified and

was blanked-out from the original release:

"For meritorious achievement as gunner while

participating in an aerial flight over ****, New Britain, on 23

September 1942. This officer and these enlisted men were crew members

of a B-17 dispatched to drop flares and bombs in a night raid on a

concentration of shipping at this enemy stronghold. After the flares

were released, at least thirty vessels were observed in the harbor.

The crew made eight bombing runs at 8,000 feet, but during each

attempt, vision was obscured by a thin strata cloud. Despite a barrage

of anti-aircraft fire from numerous ships and shore batteries, the

B-17 dived to 1500 feet and released three bombs over a group of four

vessels.

A direct hit was scored on a large cargo ship and a near miss on a

12,000 ton transport. Although the plane sustained six damaging hits

by shell fragments, it managed to escape from the hail of fire. The

courage and devotion to duty displayed by these crew members is worthy

of commendation."

Pulitzer Prize winning author Neil Sheehan describes the daring raid

of September 23, 1941 in his bestselling book “A

Fiery Peace in a Cold War”. However, there are a few facts

that were not quite correct:

"Schriever was not content just fixing B-17s for

other men in the 19th Bombardment Group to fly. He and Major John

Dougherty, a wild streak of an Irishman who was the group operations

officer, put together a headquarters strike crew. Daylight raids on

Rabaul were halted after the B-17s proved too vulnerable to the

Mitsubishi Zeros stationed there. (The Zero was the most advanced

fighter in the Pacific in 1942, only the twin-engine Lockheed P-38, of which Kenney

had a mere handful of then, came close to matching it.)"

This is true. The Japanese Zero was faster in large part

because it was not weighted-down with the gummy fuel tank sealant that

protected the plane from explosion when hot by incendiary bullets.

Louis Burleson said that the gunners would deliberately aim at the

wings of an attacking Zero and the fighter would explode in a huge

fireball.

"The 19th

switched to night attacks with flares for illumination. The Zero was

not originally meant to be a night fighter and for some reason the

Japanese never attempted to retrain the pilots and send them aloft

after dark. Schriever rigged up a flare-dropping device for the B-17

he and Dougherty flew. They would first drop flares for the other

bombers and then they themselves would bomb."

Actually, Louis Burleson rigged the flare devices, according to

specs from Schriever.

Sheehan continues describing the raid:

"On the night of September 23, 1942, they were after

ships assembling in the harbor. Jack Dougherty, who was to end his

career as a brigadier general working for Schriever, had had a lot of

experience at combat flying and thus was, by mutual agreement, the

pilot and aircraft commander. Bennie flew as his co-pilot, even though

he was senior by date of promotion. A survivor of the Java disaster,

Dougherty was doubly fortunate to have escaped in that he had been

shot down and by good luck rescued from a small island off the Java

coast. The narrowness of his encounter with eternity had not

intimidated him.

At Mareeba, in addition to plenty of flares, they

loaded four 500-pounders into the bomb racks “to be sure that we had

our amount of fun,” as Schriever put it in his after-action report.

They stopped at Port Moresby to top off their fuel tanks, then headed

with the rest of the raiding formation north across the Solomon Sea

for Rabaul. They made several passes at 4,000 feet over the wide

harbor, formed by the remnant crater of an ancient volcano after it

had erupted and exploded, dropping a sequence of five flares to enable

the other B-17s to pick out one of the estimated thirty Japanese ships

anchored there that night.

After they realized the moon was so full and bright

that night that flares were unnecessary, they decided to try their own

hand at bombing and climbed to 10,000 feet. The new and still top

secret Norden bombsight required long minutes of level flight to focus

on a target, suicide against antiaircraft fire at 4,000 feet.

Unfortunately, a cloud bank right at that lower altitude where they

had been dropping flares now obscured the ships and made it too

difficult for the bombardier to aim.

In a moment of insane inspiration, Dougherty

suddenly said, “Let’s dive-bomb the bastards.”

In reality, this was not a s spontaneous as Sheehan would like us

to think. I know that it was the dive bombing was planned in

advance because Louis Burleson specifically mentioned outfitting the

B-17 with special armor plating.

"Although Schriever later admitted he was not the

type to have thought of anything so rash and hair-raising, he did not

object. “I’ll watch the air speed and altitude,” he replied, so that

they would not dive too rapidly and tear off a wing. They could not

actually dive-bomb a ship with a B-17, but they did the next best

thing to it. To keep the Japanese from hearing the noise of the

engines as they descended and gain an element of surprise, they cut

back the throttles.

Then Dougherty pushed the wheel forward and down the

big four-engine bomber went, leveling off at 1,500 feet as Dougherty

raced straight for four large ships he could see lined up in the

middle of the harbor. “To say that AA [antiaircraft fire] was ample

would hardly cover the case,” Schriever later wrote in his report.

“Every ship in the harbor and most ground installations were firing at

us. Tracers were converging [from] so many directions that it is a

wonder they didn’t collide with each other.” The Norden bombsight was

useless at this speed and altitude. Schriever glanced at the airspeed

indicator and it was registering 260 miles per hour. In fact, no one

was ever known to have attempted bombing with a B-17 in this

harum-scarum manner.

But the bombardier, another Irishman, Lieutenant

Edward Magee, who had also escaped undaunted from the debacle on Java,

had sufficient expertise to be up to the challenge. He eyeballed the

bomb release range and angle and, when his instinct said “Now,” let a

500-pounder fly. The first bomb turned out to be a dud. With the

second, Magee scored a direct hit on a freighter estimated in the

8,000 ton class. The ship was probably destroyed instantly, as a

secondary explosion erupted from within the hull right after the bomb

struck. Magee then tried for a troop transport in the 12,000-ton

class, but he had a near miss.

As soon as the third bomb was away, Dougherty

threw the B-17 into a series of violent, evasive maneuvers, turning,

sliding from one side to another, dancing around the sky while

climbing to 4,000 feet to clear the ridge on the other side of the

harbor. Schriever was convinced afterward that Dougherty’s skill at

aerial acrobatics was what saved them from being shot down. As they

topped the ridge and were headed back out over the sea they spotted a

Japanese destroyer anchored in a bay along the island’s shore.

They had one 500-pounder left and Magee, crouched in

his little compartment under the flight deck in the nose of the B-17

and caught up in the same frenzy of combat that possessed Dougherty,

did not want to waste it. “Let’s get the son of a bitch,” he urged

over the intercom. Dougherty turned, dropped to 1,000 feet and bore

down on the Japanese warship. Unfortunately, the bomb hung up in the

rack- its release was delayed- and it sailed over the destroyer and

exploded harmlessly on the shore."

In his book, Sheehan only notes the six shell fragments that hit

the B17, but does mention that the bomber was riddled with hundreds of

bullet holes from small arms fire. Louis Burleson used to joke

that the machine gun fire sounded like rain on a tin roof and that the

metal plate he placed under is seat had a bullet hole in it after the

mission, saving him from a real "pain in the ass".

Bombing with flare

However, these improvised

B-17 flare racks has some issues, as noted in this

TIME magazine article from 1958. In a test of the new

flare racks, B-17 (41-2434) of the 30th Squadron of the 19th

Bombardment Group at Mareeba crashed into the sea near Cairns while

testing a new flare dropping mechanism. The rack malfunctioned

and the flare exploded inside the B-17 causing it to crash into the

sea, exploding on impact on 16 August 1942. The B-17 crash

occurred just inside the Great Barrier Reef a few miles north and East

of Mareeba Queensland:

"He (Gen Schriever)

learned something of the shoestring tragedies of R and D when a

B-17 fitted with a new flare-dropping rack that he had designed

caught fire mysteriously over Cairns, Australia and crashed,

killing its crew.

The investigation did

not establish conclusively that his rack was responsible, but

thereafter the device was regarded with open suspicion; no one

but Ben and a co-designer felt nervy enough to fly with it."

Recommendation for field commission

General Schriever later became the father of

missiles and space in the Air Force. General Schriever’s

recommendation for Louis Burleson reads:

Technical

Sergeant LOUIS F. BURLESON, 6882468, has been directly under my

command for over three months. During this time has performance

of duty has been superior. He has shown a keen interest in all

projects which, in any way, might improve our effectiveness against

the enemy.

He not only

installed the first flare rack in B-17 aircraft but also went on the

first two combat missions on which flares were used. His habits

and character are excellent and his attention and devotion to duty

unquestioned. It is my opinion that he is well qualified to

perform the duties of commissioned grade.

Major Bernard Schriever - November 10, 1942

During his time in Australia, Louis flew fifty-two

combat missions as a gunner and flight engineer in the remaining B17

bombers. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross on two

occasions, each time for meritorious valor in combat, and also

received the Air Medal. Louis F. Burleson’s second Distinguished

Flying Cross commendation reads:

LOUIS F. BURLESON, 6882468, Technical Sergeant,

Headquarters Squadron, 19th

Bombardment Group (H), Air Corps, United States Army.

For

extraordinary achievement while participating in the aerial flights in

the Southwest Pacific Area from December 8, 1941 to November 9, 1942.

During this period, Sergeant Burleson participated in more than fifty

operational flight missions during which hostile contact was probable

and expected. These flights included long-range bombing missions

against enemy airdromes and installations and attacks on enemy naval

vessels and shipping.

Throughout

those operations, Sergeant Burleson demonstrated outstanding ability

and devotion to duty.

Louis Burleson was transferred to Pyote Texas in

November of 1942 as a newly-minted lieutenant to serve as an

instructor of aircraft mechanics. Being a very creative fellow,

Louis invented several tools for aircraft warfare, and was transferred

to the Pentagon in Washington, DC where the Army Air Corp patented

several of his inventions.

Louis F. Burleson unit patches

|

|

|

| 5th Army Air Corp |

2nd Army Air Corp. |

315th Air Division

(Korea) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

19th Bomb Group

In Alis Vincimus |

30th Squadron, 19th Bomb

Group |

15th Air Force |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| 3rd Maintenance Squadron |

Far East Air Force |

6127th Air Terminal

Group (Korea) |

Supplying the Korean War effort

Louis Burleson volunteered to fight in Korea, and served as detachment

commander for the 6127th Air Terminal Group. The 6127th Air

Terminal Group was organized at Ashiya AFB, Kyusho, Japan on 7

February 1951, being attached to 315th Air Division, Far East Air

Forces (FEAF).

For his service in Korea as Commanding Officer of

Detachment 15 and Detachment 12, of the 6127th Air Terminal Group in

Korea, Louis Burleson was recommended to receive the Distinguished

Service Medal, for commanding the air supply lines to the Army that

delivered over 400 tons of supplies per day. The DSM, usually

given only to generals, was offered to Louis for his outstanding

contribution to the war, but he declined, stating that he was not

worthy of such a great honor. Instead he was awarded the Bronze

Star. Here is the original text of the Citation:

By direction of the President, Major Louis Francis

Burleson, AO 514246, United States Air Force, has been awarded the

Bronze Star Medal.

CITATION

Major Louis F. Burleson (then Captain) distinguished

himself by performing service in connection with military operations

against an enemy from 21 January 1951 to 4 May 1951 as Commanding

Officer, Detachment 15 and Detachment 12, 6127th Air

Terminal Group in Korea.

Though hampered by adverse weather conditions and a

shortage of personnel and equipment, Major Burleson was able to on

load and off load four hundred tons of Combat Cargo from aircraft per

day, assist in the air evacuation of the sick and wounded and assist

in the transportation for the Rest and Recuperation program.

It was through Major Burleson’s ingenuity,

initiative, knowledge of his hard and demanding job, and his devotion

to duty by undergoing many personal hardships and long hours of work

that made the Combat Cargo mission successful at these front line air

strips thereby brining great credit upon himself, the Far East Air

Forces, and the United States Air Force.

Louis F. Burleson was then assigned to Muroc AFB in

California where he was in charge of aircraft maintenance. It

was there that he became friends with Chuck Yeager, the first person

to break the sound barrier.

Military medals

Louis Burleson also volunteered for service in

Korea and was the project officer for the 6127th Air

Terminal group where he was promoted to Major and won the Bronze Star

for his Valor during an attack. His brother Vincent Burleson

also served in Korea and received the Air Medal for distinguished

aerial achievement in B-29 bombing missions.

Louis F. Burleson was injured numerous times in

WWII and Korea, most notably a back injury and a loss of hearing from

being near an explosion. His selfless devotion to duty was

apparent when he refused to seek treatment for these injuries for fear

of loosing combat status, even though he could have been awarded the

Purple Heart and transferred to a non-combat role.

His last assignment was with the 3415 Field Maintenance squadron at

Lowry AFB in Colorado.

Louis F. Burleson in 1955, at age 41

Louis Burleson was forced to accept a medical

retirement in 1958 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. As a

disabled veteran, he spent the rest of his life championing the rights

of those who were injured in service to their country.

Louis F. Burleson ribbons

|

Four Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal battles: |

1. Philippine Island

7 Dec 41 - 10 May 42

2. Air Offensive, Japan

17 Apr 42 - 2 Sep 45

3. Papua New Guinea:

23 Jul 42 - 23 Jan 43

4. Guadalcanal

7 Aug 42 - 21 Feb 43

Louis F. Burleson Service History Summary:

1935 - 1941: Crew Chief, 18th

Pursuit Group, Oahu Hawaii

1941 - 1943: B-17 Air Crew

Member, Flight Engineer, Pacific Theatre WWII

1943 - 1944: Technical inspector:

Alexandria LA

1944 - 1945: Technical

Inspector, Pyote TX

1946 - 1946 - Technical Inspector,

Clovis NM

1947 – 1950:

Supervisor

of Maintenance Security:

Muroc Air Force Base California

1950 – 1952:

Detachment

Commander, 6127th Air terminal Group, Korea

1952 – 1957:

Squadron

Commander, Lowry Air Force Base Colorado

Louis F. Burleson Service History Details

- 15 March 1935 - 29 March 1941:

18th Pursuit Group, Hawaii, service as Crew Chief for P-36's and P-40's.

- 12 March 1941 - 3 March 1943:

The 19th bomb group (30th squadron) in WWII:

-

March Field, Calif, 25 Oct 1935;

-

Albuquerque, NM, 7 Jul 1941 to 29 Sep 1941;

-

Clark Field, Luzon, 23 Oct 1941;

-

Batchelor, Australia, 24 Dec 1941;

-

Singosari, Java, 30 Dec 1941;

-

Melbourne, Australia, 2 Mar 1942;

-

Garbutt Field, Australia, 18 Apr 1942;

-

Longreach, Australia, 18 May 1942;

-

Mareeba, Australia, 24 Jul-23 Oct 1942;

-

3 March 1943 - 7 December 1943:

19th bomb group HQ: Served as Group Technical Inspector

-

10 December 1943 - 20 December 1943:

517 Base HQ, Alexandria La.: Air

Inspector

-

20 December 1943 – 3 March 1944:

469 CombTngSchMaint Sec1 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU) Alexandria

LA: Production line maintenance inspector

-

3 March 1944 – 30 June 1944:

221 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU),

Alexandria LA: Assistant Technical inspector Aircraft Eng O

-

30 June 1944 – 22 July 1944:

221 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU),

Alexandria LA:

Assistant Technical inspector Aircraft Eng

O

-

27 July 1944 – 7 November 1944:

220 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU)

Ardmore OK.:

Technical Inspector

-

7 November 1944 – 31 December 1944:

Sec. A, 236

Combat Crew Training Squadron

(CCTs), Pyote TX:

Technical Inspector

-

1 January 45 – 30 June 1945:

Sq A, 236

Combat Crew Training Squadron

(CCTS), Pyote TX:

Technical Inspector

-

1 July 45 – 14 November 1945:

Sq A, 236

Combat Crew Training Squadron

(CCTS), Pyote TX.:

Technical Inspector

-

15 November 1945 – 20 November 1945:

Sq A, 4141 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU),

AB, Pyote TX:

Technical Inspector

-

21 November 1945 – 31 December 1945:

234 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU),

Clovis NM:

Technical Inspector

- 1 January 1946:

234 Army Air Force Base Unit (AAFBU),

Clovis NM:

Technical Inspector

- 1 August 1946 – 4 September 1946:

7536 TDY HQ 15 AF 234 AAFBU AAF Clovis NM

-

5 September 1946 – 30 September 1946:

7536 technical

inspector air inspector SEC Headquarters 15th

Air Force 234 AAFBU AAF Colorado Springs CO

-

1 October 1946 – 321 December 1946:

7536 technical

inspector air inspector SEC Headquarters 15th

Air Force 234 AAFBU AAF Colorado Springs CO

-

20 September 1950 – 19 June 1952:

FEC

- 21 May 1952:

Aircraft Maintenance officer PAM 32, 6127

ATCAP 075

- 7 December 1953:

Supply Officer PAM 27, 3415 Maintenance squadron

-

25 July 1953 – 23 August 1953:

4311 Assistant Chief of Maintenance, 3416

Field Maintenance squadron, 3415 Tactical Training Wing, Lowry ABF

Colorado

-

24 August 1953 – 16 September 1953:

4311 Assistant to Chief of Maintenance,

3416 Field Maintenance squadron, 3415 Tactical Training Wing, Lowry

ABF Colorado

-

17 September 1953 – 6 December 1953:

4311 Assistant to Chief of

Maintenance, 3415 Field Maintenance squadron, 3415 Tactical Training

Wing, Lowry ABF Colorado

-

7 December 1954 – 28 February 1954:

6421 Supply Liaison 0, 3415 Field

Maintenance squadron, 3415 Tactical Training Wing, Lowry ABF Colorado

-

1 March 1954 – 20 April 1954:

6421

Supply Liaison 0, 3415 Field Maintenance squadron, 3415 Tactical

Training Wing, Lowry ABF Colorado

- 21 April 1954:

4344 3415 Field Maintron acftshops

officer, 3415 Field Maintenance squadron, 3415 Tactical Training Wing,

Lowry ABF Colorado

Personal

Notes:

Louis was originally named “Kenneth”, but his

mother changed his name to the Catholic name “Louis” in 1918 after

converting to Catholicism.

Louis married

Virginia

Virginia

attended the University of New Mexico and earned a degree in general

studies in 1942. Ironically, Lou and Ginger both lived in New

York City in the 1920's and lived a few blocks from each other for

several years. They both remembered the construction of the

Empire State Building, but it would be many years before they would

meet in Albuquerque. They met while Ginger was playing with her

pet rabbits on her front lawn and Lou drove by in a jeep. Lou

stopped to introduce himself, and they immediately found themselves

attracted to each other. They were married in September of

1941.

Lou once remarked that the best advice he ever

received from his father was the saying "There's always room at the

top". He interpreted his father's advice to mean that a person

could always rise to the top, and the only impediment to achievement

was a lack of confidence in your own abilities.

Lou was an expert marksman, and was rated as an

expert rifleman by the U.S. Army Air Corps. (see appendix) This

is not surprising, because the number one priority with the Burleson's

was to teach their children proficiency with a rifle. Superior

marksmanship was a very important skill, and was held in high regard

by all past generations of the Burleson family.

Lou enjoyed hunting, and at one time owned more

than 15 rifles. Lou passed the Burleson tradition of

marksmanship on to his son, Don.

Lou and Ginger had one child, Donald Keith

Burleson, while they were stationed at Lowry ABF in Aurora Colorado.

Following Lou's retirement in 1958 with the rank of Lieutenant

Colonel, the couple moved back to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Lou continued the Burleson tradition of serving

Oyster Stew on Christmas Eve, much to the disgust of his family.

Other family traditions were Christmas stockings filled with fresh

oranges and nuts. Lou also enjoyed playing Cribbage and

Blackjack with his son.

Louis developed a severe hearing loss and crippling

arthritis after his retirement from the Air Force, but he always

maintained a cheerful disposition and occupied his time by doing

volunteer work for the Republican party. An avid reader, Lou

spent his last days keeping up with current political and national

events.

Virginia & Louis F. Burleson circa 1966

Virginia, Donald and Louis Burleson, their last Thanksgiving together,

November 1974

As Lou's health continued to deteriorate, he was

eventually confined to a wheelchair, and died on September 26, 1975 at

the age of 60, Virginia following him in death on March 25, 1976.

Virginia died at 56 years of age on her son Donald's 20th birthday.

She was born in 1920, and he was born in 1956 . . .

Louis was buried in the Santa Fe National Cemetery

with full military honors. His wife Ginger died six months later

from lung cancer, and she is buried next to him.

*******************************************************

Louis was

evacuated from the Philippines on January 27th 1942 in

a B-25 bound for Darwin Australia:

Lt Wade in LB-30, No Al-509, and Lt Funk in B-24A

No 40-2376 arrived from Darwin at 1245 and 1300 respectively. Between

them they evacuated the following officers and men from Del Monte,

Mindanao, P.I.

|

1st Lt

|

Huse J.E.

|

0-21777

|

|

2nd Lt

|

Railing

W.M.

|

0-398588

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Crumley

T.J

|

6203446

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Doucet A.

|

6229636

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Fleming J.O.

|

6537402

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Henderson R.E.

|

6551252

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Holub A.

|

6541498

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Hunley C.L.

|

R-94744

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Lane R.C.

|

6526355

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Newman G.V.

|

6074224

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Nicholas r.R.

|

6230961

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Schumaker C.S.

|

6635129

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Small B.S.

|

R-326531

|

|

M/Sgt

|

Stewart A.E.

|

6225863

|

|

T/Sgt

|

Burleson L.F.

|

6882468

|

|

T/Sgt

|

Deterding F.M.

|

6858419

|

|

T/Sgt

|

Nelson O.W.

|

6353537

|

|

T/Sgt

|

Shook P.E.

|

6658245

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Baierl H.S.

|

6524288

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Brown R.D.

|

6911499

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Davis R.R.

|

6929991

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Dillon R.W.

|

6268737

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Faulkinburg J.F.

|

6555933

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Furnald R.

|

6556239

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Pack H.

|

6264846

|

|

S/Sgt

|

Rose E.J.

|

6241916

|

|

Sgt

|

Brewer W.E.

|

6297825

|

|

Sgt

|

Clark W.E.

|

6574184

|

|

Sgt

|

Lawson Jr G.W.

|

6914301

|

|

Sgt

|

Makela J.E.

|

6579404

|

|

Sgt

|

Marquardt D.J.

|

6914322

|

|

Sgt

|

McDonald J.H.

|

6297745

|

|

Sgt

|

Monaghan F.S.

|

6580288

|

|

Sgt

|

Murdock H.

|

6579298

|

|

Sgt

|

Taylor M.E.

|

6950938

|

|

Sgt

|

Whitehead

|

6557024

|

|

Cpl

|

Brown D.W.

|

6296430

|

|

Cpl

|

Elliott R.O.

|

6935516

|

|

Cpl

|

Elmer A.R.

|

6937691

|

|

Pfc

|

Tomerlin B.E.

|

6578477

|

|

Pvt

|

Whipp L.D.

|

19050622

|

|

Pvt

|

Wilfley J.J.

|

17015875

|

|