|

|

Bernie Schriever was a newly-minted Major fresh out of Stanford University with a masters degree in engineering and a bold plan. He and my father (Louis F. Burleson) hatched a plan to surprise the Japanese with an attack so bold that it was almost suicidal. In total darkness, one B-17 crew would drop flares to light-up the ships in the harbor and then dive below the flack, directly into a hail of bullets and dump a bomb right on the deck of an enemy ship!

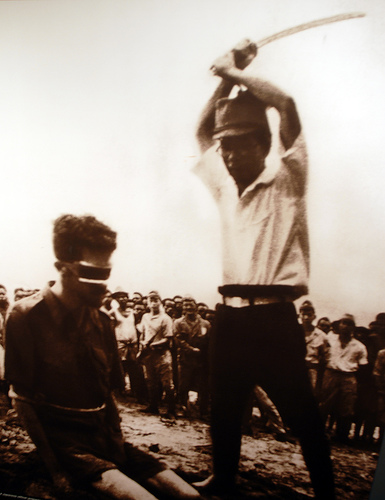

A B-17 is a large 4 engine machine, and this mission was carefully planned and executed. My father added a half-ton of hardened steel armor to protect the pilot and crew from the machine gun bullets, and Schriever carefully calculated the maximum amount of G force that the B-17 could take before the wings would fall off. There was no question that the aircraft would be heavily damaged and they calculated their probability of success at 50% and asked for volunteers, quickly finding a dozen brave men to fill the seats. It was a very risky endeavor. Americans knew that the Japanese did not like to take prisoners and American airmen would be beheaded.

My father designed the flare racks and volunteered to fly on this mission as

flight engineer, manning the top turret gun on the B-17. It's not designed to do that! This bold planned called for some serious innovation. My father installed the flare racks and Schriever calculated the exact amount of bombs and fuel weight and how far he could push the envelope. The Japanese were not going to sit back quietly as their ships were destroyed, and success depended on a steep angle of attack, pulling enough G forces to bend the wings, but not break them.

Of course, there were those narrow-minded airmen who called the plan crazy

and mocked them, saying that "It's not designed to work that way".

Flying into a hailstorm of bullets To achieve maximum surprise, they left before midnight to as to hit Rabaul right before sunrise. This was serious business, a high risk, high reward attack. Each man was ordered to write a last letter to their family and make out a last will and testament before leaving on the mission. This recollection is from an article about General Schriever in “Air Force” magazine: “They flew in a formation of about a dozen B-17s in a night raid on Rabaul. Their airplane carried the flares and half the regular bomb load. The flare system worked well, but Schriever wanted to check on the bombing results, so they made another circuit over the target area. Flak was heavy but ineffective at the 10,000-foot altitude from which they were bombing. As they turned, the No. 3 engine burst into a ball of flames. Dougherty, in the left seat, feathered the prop and shut the engine down. They still had bombs on board but did not want to set up another bombing approach. A quick conference on the intercom led to a decision: They would dive-bomb the ships in the harbor.” According to my father, the small arms fire was greater than expected and as the B17 nosed down below 2,000 feet the bullets hitting the ship sounded like rain on a tin roof, with bullets flying everywhere. The B-17 was badly damaged, flying on only 3 engines and hit by flack in six places and littered with hundreds of bullet holes. Through good piloting, Schriever managed to limp back to Australia where not a single square foot of the plane was not pierced by bullets. After the attack, my father found a machine gun bullet embedded in the steel armor that he welded to the bottom of his seat, and he joked that his planning-ahead saved him from a huge pain in the ass. Bernie Schriever got noticed by the top brass, eventually rising to 4 star general in the Air Force. Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado is named after Bernie Schriever. My father received the Distinguished Flying Cross for this mission. Here is the citation of the B-17 dive bombing raid from military records. Rabaul harbor was still classified and was blanked-out from the original release: "For meritorious achievement as gunner while participating in an aerial flight over ****, New Britain, on 23 September 1942. This officer and these enlisted men were crew members of a B-17 dispatched to drop flares and bombs in a night raid on a concentration of shipping at this enemy stronghold. After the flares were released, at least thirty vessels were observed in the harbor. The crew made eight bombing runs at 8,000 feet, but during each attempt, vision was obscured by a thin strata cloud. Despite a barrage of anti-aircraft fire from numerous ships and shore batteries, the B-17 dived to 1,500 feet and released three bombs over a group of four vessels. A direct hit was scored on a large cargo ship and a near miss on a 12,000 ton transport. Although the plane sustained six damaging hits by shell fragments, it managed to escape from the hail of fire. The courage and devotion to duty displayed by these crew members is worthy of commendation."

It's this type of innovation that won WWII, open-minded airmen who were not

afraid to push the limits and try new approaches to achieve their goals.

|

|

|